Twenty years ago, the first GMO seeds hit the market. In the decades that followed – as more GMO varieties were adopted and the seed sector rapidly consolidated – ethical, political, legal, environmental, economic and social concerns for the technology have emerged. While many farmers say they are pleased with GMO varieties, many others are disappointed, finding mixed results or facing new problems in the extremely concentrated and corporate-dominated seed sector. These problematic trends affect all farmers, whether or not they plant GMO seeds.

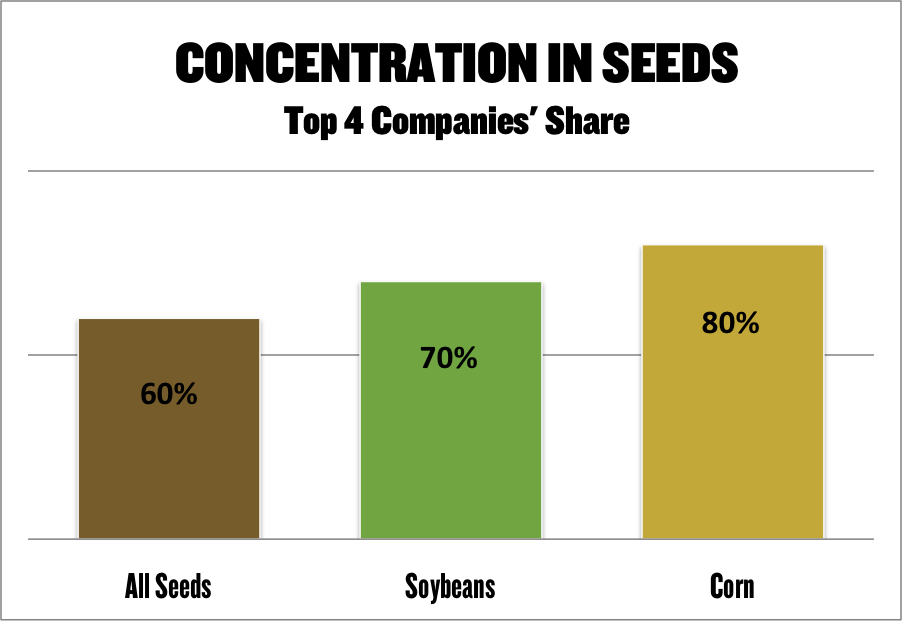

Since the commercial introduction of GMOs, the seed industry has rapidly consolidated. Today, just four companies control almost 60% of the seed market. For certain crops, the market is even more concentrated. The “big four” seed companies – Monsanto, DuPont, Syngenta and Dow – own 80% of the corn and 70% of the soybean market.

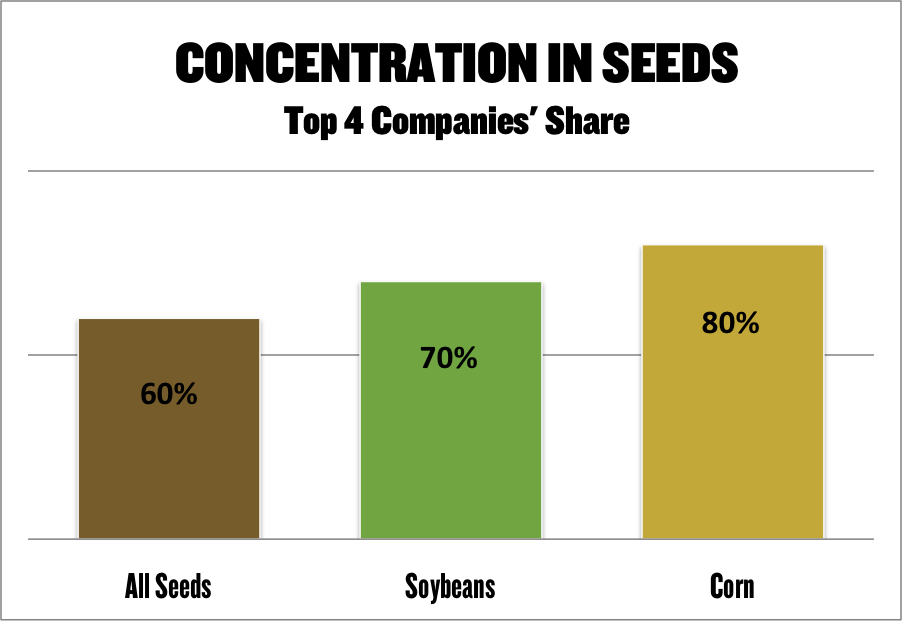

This concentration has made a huge dent in farmers’ pockets. USDA data show that the per-acre cost of soybean and corn seed spiked dramatically between 1995 and 2014, by 351% and 321%, respectively. [1] Those costs far outpaced the market price farmers received for corn and soy, leaving them tighter margins on which to run their farms.

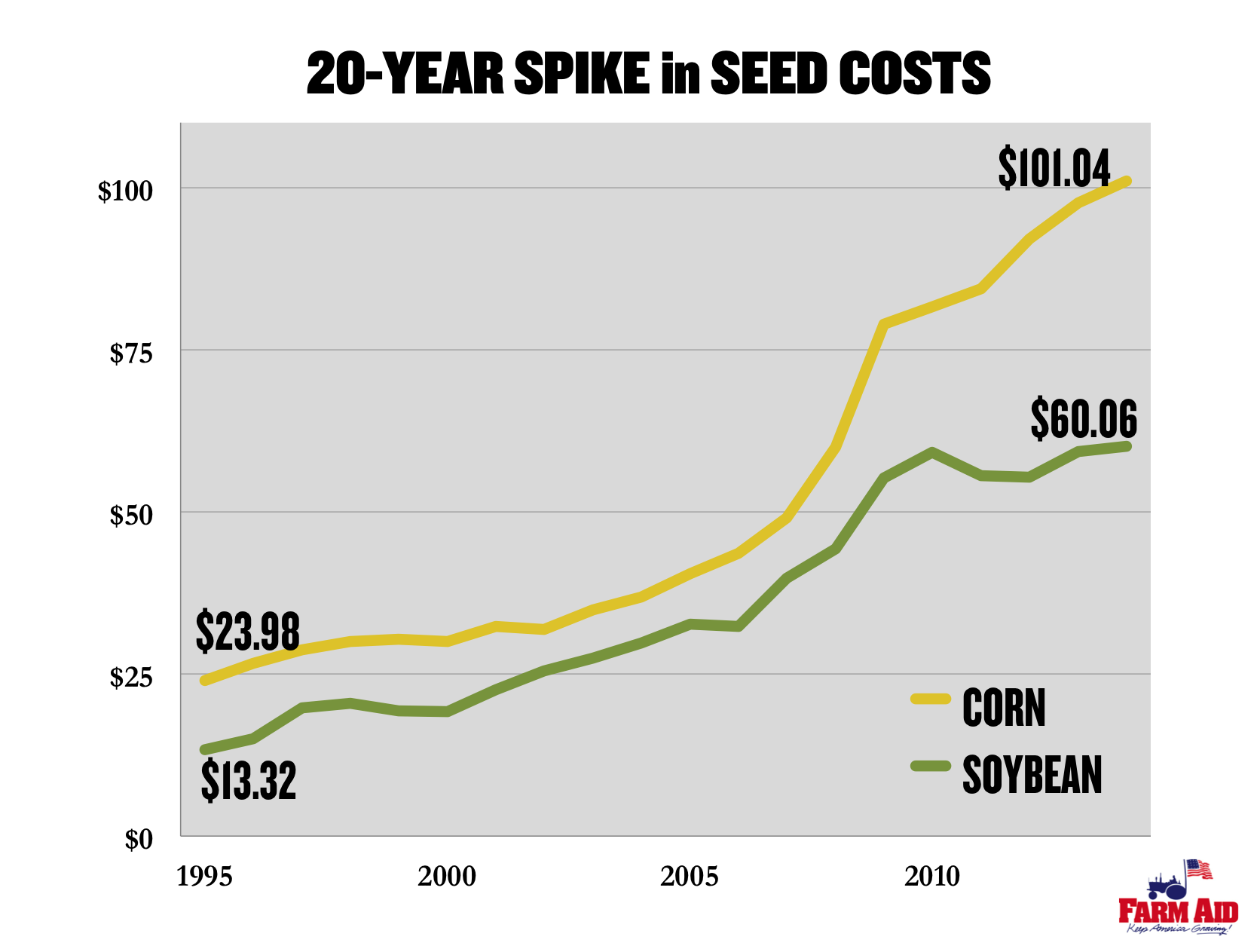

GMO contamination is well documented. According to the International Journal of Food Contamination, almost 400 cases of GMO contamination occurred between 1997 and 2013 in 63 countries. Part of the problem is the very nature of nature. Many plants are pollinated by insects, birds or wind, allowing pollen from a GMO plant to move to neighboring fields or into the wild. This “genetic drift” illustrates the enormous difficulty in containing GMO technology. Not only is genetic drift impossible to prevent, inadequate regulation also fails to hold seed companies accountable for any resulting damages and ultimately puts the onus on farmers who have been the victims of contamination.

For farmers, the consequences have been severe. Contamination can spark dramatic economic losses for farmers who face rejection from export markets that ban GMOs. Organic farmers suffering contamination can lose their organic certification and the premium they earn for their organic crop.

As consumer demand for non-GMO products expands, farmers are looking for opportunities to diversify into non-GMO markets that pay higher prices. But the inability of companies to properly segregate GMOs from conventional varieties continues to threaten these options for farmers.

GMO agriculture has led to superweeds and superpests that are extraordinarily difficult for farmers to manage.

Farmers affected by resistant pests must revert to older and more toxic chemicals, more labor or more intensive tillage, which overshadow the promised benefits of GMO technology.

Of particular concern is the overuse of glyphosate, a broad-spectrum herbicide commercially found in Monsanto’s Roundup, used with seeds engineered to withstand its application. Between 1996 and 2011, U.S. herbicide use grew by 527 million pounds, mostly from glyphosate. There are now at least 14 species of glyphosate-resistant weeds throughout the country, and almost double that number worldwide. This very scenario was forewarned in a 2010 report from the National Academy of Sciences, which cautioned that the overuse of glyphosate would render it useless. There are similar reports of bollworm resistance to the Bt toxin in GMO cotton.

Herbicides, including glyphosate, can also increase plant diseases by altering plants’ ability to absorb nutrients and reduce soil health by killing microbes. These chemical-dependent strategies, peddled by major chemical and biotech companies, will keep farmers dependent on increasingly toxic pesticides in a race that nature always wins.

Perhaps the best-known event illustrating the importance of genetic diversity in agriculture is the Irish potato famine. In the 1800s, much of the Irish population depended on the “lumper” potato almost exclusively for their diet. The country was a veritable monoculture – a great vulnerability that revealed itself when blight spread rapidly through the countryside, devastating the crop, the Irish population and its economy.

Lessons from the Great Famine should be heeded. The prevalence of GMOs in major field crops threatens the genetic diversity of our food supply. Genetic diversity helps individual species adjust to new conditions, diseases and pests, and can aid ecosystems in adapting to a changing environment or severe conditions like drought or floods. Climate change presents these exact challenges and farmers need as many tools as possible to address them – right down to the genetic code.

Traits like drought tolerance are complex, driven by several genes. Genetic engineering generally targets one gene at a time. Tools like traditional breeding techniques and seed banks, which preserve the genetic diversity of seeds, are proving more effective at developing drought tolerant crops. Unfortunately, extreme consolidation in the private seed sector has coincided with the decline of public investment in traditional seed and breed development. At a time when farmers need more options, not fewer, these programs need to be bolstered.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that GMOs could be patented, but patents are now key to furthering the power and profits of biotech companies.

Farmers who buy GMO seeds must pay licensing fees and sign contracts that dictate how they can grow the crop – and even allow seed companies to inspect their farms. GMO seeds are expensive and farmers must buy them each year or else be liable for patent infringement. And while contamination can happen through no fault of their own, farmers have been sued for “seed piracy” when unauthorized GMO crops show up in their fields.

Patents make independent research on GMOs difficult. Farmers must sign agreements that prohibit them from giving seeds to researchers or carrying out their own research. Meanwhile, researchers cannot conduct studies on GMOs without a license from the seed company, allowing companies to restrict the nature of research on their seeds.

There is no silver bullet for the numerous and complex challenges farmers face on their farms. In a time of mounting problems like climate change and market concentration, technology should expand the tools available to farmers, not restrict them. That’s why Farm Aid calls for:

– Last updated: March 17, 2016 –